Bill Culbert’s strategy for working developed from and through the painting of his early years to the late nineteen-fifties. His post-cubist painting then turns towards construction, and becomes almost serial. By the mid-sixties, this constructive axis of the work could almost be confused with some aspects of kineticism and the Groupe Recherche d’Art Visuel in France. His kinetic-field and camera-obscura pieces, the more pure object-of-light pieces were made at this time, and his Cubic Projections of 1968 has indeed been much imitated. But the work was always more questioning, and with revelatory humour, than merely perceptual. Perhaps this led to the more ready-made and bricolage works – the suitcases, the doors, windscreens, headlights and parts of the 2CV, the plastics, the lampshades, the refractions of wine. His assembly of lamps, tables, chairs, domestic objects, picked from the refuse tips of the Luberon valley were put to work in the cluster of rebuilt houses and studios in the village of Croagnes, using and making available light and light available.Through all the work runs the distilled optimism of the modernist, the structured enquiry of his entire project.

The intruded light tube, the fluorescent strip in various sizes and combinations is one of the parts of his work. Light tubes have been imposed on large photographic installations, as in Weather 1988. They have been installed from wall to floor and floor to wall and through furniture, even imposed on Alvar Aalto’s small table in Table Lamp II 1982. They were thrust through the windows of a full scale model of the Serpentine Gallery windows in An Explanation of Light 1984. In floor pieces such as Flat Light House from 2008, or Flotsam 1992, or the seemingly randomised Spacific Plastics of 2001, in Pacific Flotsam of 2007, the intruded light tubes irradiate a seemingly dishevelled scattering of dicarded plastic containers to form an enormous glow of coloured light. Culbert always reminds us of the pleasure of finding dicardable materials for re-use. The window frame, the casement of light, has also often figured in the work. It has gone as far as the intimated flat-pack of Flat Light House from 2008. Besides their resource as parts of works, the windscreens and panels from Citroen 2CV cars have been used by Culbert as more domestic shields and tables, as they are used in the localities of rural France as canopies over porches and doors.

We are witnessing the last days of the incandescent light bulb, to be replaced by more energy-efficient forms. Bill Culbert celebrates this with an editioned piece in the form of The Last Incandescent Light Bulb, where a clear light bulb is used as the stopper of a glass decanter, a vessel often seen in the Culbert household. Its image was first used as a photographic work Decanter from 1985.

There have always been the photographic works at a parallel to the objects and installations. There is always a duality in the photographic works, an ambiguity that posits the question of what is the actual work: the subject of the photograph or the photograph itself, the issues of choice of black and white and colour. An early compilation of such black and white pieces was called Extant Works and Sources, 1984. Perhaps more importantly, they all have a necessary myopia of focus, a re-iteration of the themes of the work, the lampshade armatures at sunset, the empty abats-jours.

The work is also the drawing of built pieces and pieces to be built, often a working inventory, the instructions for making them. The drawings were, at times, also pure form, with the swift and spare open line begun in his earliest work, enhanced by his trusted Parker 51 Fountain Pen, designed by Moholy-Nagy.

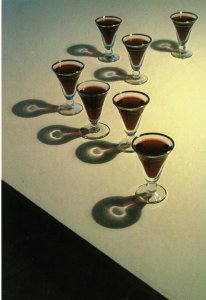

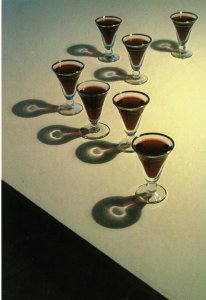

There is always wine, and the consequence of wine poured into a glass, its reverse perspective, its shadow, the lucidity of it. ‘Small Glass, Pouring Light’, 1983 is the seminal work, now permanently installed in the Chateau d’ Oiron in the Poitou region of western France. Bistro glasses of a particular refractive index, filled with red wine, re-form the light bulbs above them onto the table – a work of mysterious calm, generously and silently inviting the viewer to participate in the refreshment of the work.

The work of Bill Culbert is of a different legacy to the reassembly of Duchamp and Schwitters. There is always an affirmation of the balance between art and living, the fuss-less ‘bien-fait’ of Creation Permanente of Robert Fillou, a celebration of quotidian ordinariness. In his oeuvre there is enormous width and range, far more so than that presumed for some acclaimed artists working in France and Britain in a most overblown time. He is one of very few really radical figures who did not settle for manufacture, brand and production – a distinct virtue of his partial neglect.

2009-2019